|

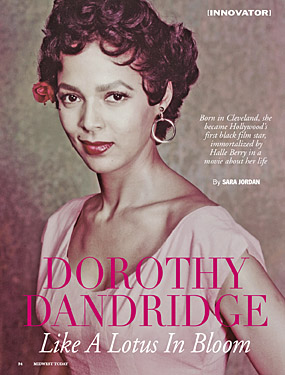

Dorothy Dandridge |

||

| Halle Berry portrayed her in a movie, and Beyonce sang about her on MTV. But most movie goers don't know about Cleveland, OH, native Dorothy Dandridge, the first African-American actress to be nominated for an Oscar. | ||

|

|

||

Dorothy believed she could have “captured the world” if she had only been born white. A transcendent figure, she was dubbed “our Marilyn Monroe” by rival black performer Lena Horne. When Dandridge died suddenly on the verge of a comeback, it was unclear if it had been a tragic accident or a self-fulfilling prophecy. On November 9, 1922, aspiring performer Ruby Butler Dandridge entered Cleveland’s City Hospital to give birth to her second child. She had just left her husband, Cyril, vowing to give her children a better life away from that “mama’s boy.” When the baby was born, Ruby decided to give her an elegant name that she felt would look good on a movie marquee: Dorothy Dandridge (though she was later nicknamed “Dottie”). The child was beautiful and light-complected due to her bi-racial heritage. Cyril was a mulatto, and Ruby had Jamaican, Native American, and Spanish blood. Ruby told the girls that Santa Claus was coming and they needed to hide. But while upstairs, the sisters eavesdropped on their mother’s conversation, and realized it was their father who was visiting. Ruby and Cyril argued intently. “Vivian and I began to cry,” Dottie remembered, “We cried because it was fearful and violent below, and we didn’t know what was going on or why.” Dorothy wouldn’t meet her father until she was well into her 30s. She spent her early years conjuring up stories concerning his whereabouts to keep other children from making fun of her. She wondered why her dad had never been strong enough to insist on meeting her. Cyril, realizing Ruby wasn’t coming back with their daughters, filed for divorce in June of 1924. As much as Dorothy needed a father figure, Ruby tried her best to compensate. Realizing her girls were talented from a young age, she arranged for them to sing and dance for some of Cleveland’s churches and social groups. “Colored churches” were full of potential for exposing the girls’ talents. Ruby herself started performing at church gatherings and at black women’s groups. She recited poetry, sang and danced, doing whatever she could to make ends meet. The two sisters’ singing venture was successful, and the newly formed “Wonder Children” were bound for a five year tour of the South. Their mother arranged all routines and hired a pianist named Geneva Williams to also chaperone the girls. Williams soon moved in with them and began teaching the girls singing, dancing and piano. They were too young to realize it at the time, but Geneva became intimately involved with their mother, and soon took on a disciplinarian role, which often resulted in violent outbursts aimed at Dorothy. In 1930, Ruby and her children moved to Los Angeles, hoping to advance the girls’ careers. By 1934, Dorothy was appearing in bit parts in films. At that time, the family was living in Watts. Dottie feared the whites who lived in the area and had many negative encounters with them. Most incidents included white men becoming fresh with her. They made overtly sexual comments and gestures toward her. Her white friends’ parents didn’t allow Dorothy to visit their homes. She also witnessed the widespread use of alcohol and drugs in the slums. She vowed to never get caught up in that kind of world. In later years she would fail to keep that promise. In the late 1930s, Ruby decided to send Dorothy and Vivian to a dance school. She also recruited Etta Jones to be the third member of the act. The group then became known as The Dandridge Sisters. Radio station KNX in Los Angeles held a talent contest that the group decided to enter. As the only black group, Ruby thought it best if the girls tried to imitate the Andrews Sisters. They won first place in the contest and were soon offered a six month gig in a traveling circus destined for Hawaii. Dorothy had a blast there and became more confident and outgoing. It was while on the Islands that talent agent Joe Glaser saw them perform, and decided the sisters would be great for the Warner Brothers movie, appropriately entitled “Go- ing Places.” The film was a success, and a string of “musical shorts” were soon made. By that time Dorothy was 15 years old and becoming a striking beauty. Glaser was so impressed by the group, that he had them booked at the prestigious Cotton Club. Before they knew it, the girls were singing with Cab Calloway in his show and also appeared on radio and stage with Duke Ellington. Dandridge then set her sights on Europe, where The Dandridge Sisters played the London Palladium among other venues. When World War ii broke out, tours were canceled, and their careers slowed down. Etta Jones then left the group to get married. Dottie longed to get married herself. In 1944 she made the acquaintance of Harold Nicholas, of the famed Nicholas Brothers stage act. They became fast friends, even though they ran in different circles. He was a notorious ladies’ man, and Dorothy had a reputation as a soft-spoken lady. He wanted to be more than friends, but Dottie put his advances on hold for the moment. When Vivian left to launch a solo career, Dorothy tried out for a role in the first integrated musical entitled “Meet the People.” It was such a big hit, that Hollywood wanted to do a film version of it. Dandridge, feeling she would be a shoe-in, lobbied to get a part. MGM planned to make the movie. Upon speaking with studio officials there, Dorothy learned the film would feature an all white cast instead. One exec told her, “The South isn’t ready for colored actors. The picture would get shut out of a lot of key spots if it were made like the play. I’m afraid there’s no place for sentiment in this business. We’d like to use more people from the play, but it just can’t be done.” Despite that bitter disappointment, Dandridge was confident in her ability to get work on the stage, and as a singer. By then, she was spending more time with Harold. He asked her to marry him, and she accepted. They barely knew each other, and Dorothy was not naive to the fact of what a fast-paced life Harold led. He was wild and outgoing. Dottie was shy and reserved, intimidated by the opposite sex. Her friends called her “The Lady” as she never smoked, or drank, (even coffee). She preferred fancy evenings out to dining in, enjoying her favorite meal of chitlins and greens, which she ate only once a week to keep a svelte figure. She exercised all the time, including lifting weights and doing aerobics. As a homebody, Dorothy also spent time scrapbooking, saving various clippings pertaining to her career, and spent long stretches on the phone with friends. Despite the obvious differences between them, Harold finally wooed Dottie, and the two married on September 6, 1942. A few months later she discovered she was pregnant. Because Harold traveled extensively in Europe, Dandridge filled her time by studying at the Actor’s Lab where she became friends with Marilyn Monroe and Ava Gardner. Even though she was a high school dropout, was married and had a child on the way, Dorothy felt liberated and enjoyed acting and learning more about her craft. The day Dandridge went into labor on September 2, 1943, she ignored the pains because her husband was still in Europe, though he was due home later that day. As the contractions got closer together, and the pain intensified, she finally made her way to the hospital. The birth proved a difficult one. Nevertheless, the baby, which she named Harolyn Suzanne Nicholas, seemed alright and Dorothy believed that the child would bring her and Harold closer. Sadly, that was not to be the case. Lynn, as she was called, was a happy child and the light of Dorothy’s life. However, by the time her daughter reached pre-school age, it became clear the child was not normal. She still couldn’t form words, only grunted, and seemed to be in a world all her own. Devastated, Dandridge took her daughter to every doctor and specialist she could find. She was told to do many at home remedies including hot baths and cold compacts, to no avail. Dottie tried to enroll the child in school, but no one would take her. She worried that her delay in going to the hospital may have harmed her child. But as she later learned, the surgical forceps used by the doctor during delivery damaged her child’s head. Nevertheless, Dottie always blamed herself for Lynn’s health issues. When she received a prognosis of the child’s condition, the verdict was grim; Lynn was mentally retarded and would have the mental capacity of a four year old for the rest of her life. Dorothy was devastated. Harold was quite indifferent to the situation at home. He spent most of his daughter’s early years pretending nothing was wrong, and felt as long as he bought his family nice things, all the problems would go away. He toured extensively in Europe, living the life of a bachelor. Dottie wrote to him constantly, pleading with him to help her with Lynn and to come back home. She begged him to accept the child as she was, and to be content as a married family man. He never replied to the letters, and his money stopped coming in the mail. When Dorothy finally succeeded in contacting him, he told her he liked his care-free life in Paris, and that their marriage was over. Dandridge was distraught and worried how she would make ends meet as a single mother. She raised Lynn herself for many years, until the child became increasingly harder to control. Dorothy, in a desperate state, sent her to go live with “aunt” Geneva and her mother Ruby. When that proved unsuccessful, Dandridge placed the child in a private institution. Realizing she needed to work to sustain her lifestyle, Dorothy went back to acting. She appeared as a singer in “Hit Parade of 1943,” and a few uncredited roles, including a small part in the Claudette Colbert war classic, “Since You Went Away.” Her film career remained lackluster through the rest of the decade. In April of 1951, Dottie made the acquaintance of Earl Mills, a man who was to become her manager and life-long friend. He was impressed by her singing and beauty, and became smitten with her immediately. He told her he could help her career. Dottie, ever self-sufficient, told him she was making a film entitled, “Tarzan’s Peril,” and that his services wouldn’t be needed. In the film, she played an African Queen who needs saving in her own jungle. After realizing the role unfairly exploited her talents and looks, Dorothy decided to seek the services of Earl Mills after all. She decided to take a break from moviemaking, and returned to the nightclub scene. In May of 1951 she opened in Hollywood’s top club, the Macombo, with the Desi Arnaz Band. That same year she became the first African American to perform in the Empire Room of New York’s Waldorf-Astoria Hotel. Dandridge also toured venues in Miami, having to stay outside the city limits, as it was illegal for non-whites to live in the city. At one of these engagements, when she asked where the restrooms were, she was handed a plastic cup. Soon after, Dandridge returned to Hollywood where MGM was making an all-black drama called “Bright Road.” She played an Alabama schoolteacher, and began the filming in August of 1952. Her co-star was an up-and-coming actor by the name of Harry Belafonte. The two would soon become lifelong friends. After the movie’s release, Dorothy resumed her nightclub act, touring in South America. She liked the fact that they were more accepting of a black performer and she was treated as an equal. Dorothy dated Gerald Mayer, the director of “Bright Road,” as well as actor and Kennedy spouse, Peter Lawford. He always maintained they were “just good friends.” However, Lawford had very few female acquaintances who were “only just friends.” Dottie also became involved with a millionaire from Rio de Janeiro named Christian Marcos, but the affair was short-lived. With her career on the rise, she appeared on the covers of several magazines. Even though she was a well-established star, overtly racist comments and actions would follow the rest of her career. She told People Today in 1953 that, “To be a siren of song, one needs more than talent, looks, and voice. One needs understanding of people. At first I was afraid they wouldn’t like me. Then I realized the first step in that direction was to like them, and to assume they would like me.” The magazine referred to her as a “bronze bombshell” and featured her on the back cover. Earl Mills soon became aware that director Otto Preminger was casting his new film entitled “Carmen Jones,” an Americanized version of the Bizet opera with lyrics by Oscar Hammerstein. It was to be the big-budget film and musical, with an all-black cast. Mills knew his client had to get a role in it. He arranged for Dorothy to meet with the Austrian director to discuss parts. Preminger wanted Dottie to read the part of Cindy Lou, who is the quiet and submissive girlfriend of the male lead, who gets dumped for Carmen. Dandridge told him that she was only interested in the lead role. Preminger felt she was too sweet and innocent to play the rough and tumble seductress. Dottie took the script home and reluctantly read it. Her mother and manager insisted she take the role offered to her, but Dorothy had other plans. She purchased a sassy short wig, a billowy skirt and low cut blouse that she wore off the shoulder. She met with the director and read a few of Cindy Lou’s lines in a provocative way. Preminger was shocked, but thrilled that he had found his Carmen. Ironically, Dandridge then had doubts she could play the role. Always battling low self-esteem, she argued that now that she had proven she could get the part, she didn’t need to actually play it. Otto and Earl finally convinced her she had what it took. By that time, she was becoming friendly with Preminger. She cooked for him, and soon after the two began dating. He was like no other man she had ever known. Harry Belafonte was cast as Carmen’s love interest, and Pearl Bailey and Diahann Carroll co-starred. Only Bailey would do her own singing, as the rest of the cast’s voices were dubbed, despite Dandridge and Belafonte being professional singers. Dottie’s voice was dubbed by then-teenaged opera singer Marilyn Horne. Dorothy spent hours a day lip-syncing to Horne’s records to obtain all the proper nuances. Carroll, in her debut movie, would achieve stardom and later went on to star in the TV show "Julia" in 1968. Thus Diahann became the first African American actress to star in her own television series as a non-domestic. The film was a major success, winning a Golden Globe Award for Best Musical Motion Picture of 1954, and an Audience Award from the Berlin Film Festival in 1955. The next few months would center around movie premieres and publicity shoots. It was rumored that Dandridge would receive an Academy Award nomination for her performance. She only smiled at the notion, doubting it would happen. Later that year, Dottie became the first woman to be featured on the cover of Ebony magazine, and she became the first African American to appear on the cover of Life (on November 1, 1954). In February of ’55, Dorothy became the first black woman to be nominated for an Oscar in a leading role. She was the third black performer to be nominated in general after Hattie McDaniel for Best Supporting Actress in “Gone with the Wind” (1939), and Ethel Waters in the same category for her 1949 role in the film “Pinky.” “Who’s Who in Hollywood” figured Dottie was sure to win the award. Dorothy didn’t want to jinx it. To ensure the nominees would attend the ceremony, all were made presenters throughout the evening. Dorothy was the first black to be an award presenter. She gave the Academy Award for Film Editing to Gene Milford for “On the Waterfront.” She felt very honored, and didn’t take the job lightly. The women on the “Best Actress” ballot were Audrey Hepburn (in her debut role) in “Sabrina” with Humphrey Bogart and William Holden; Grace Kelly for “The Country Girl,” opposite Bing Crosby and Holden; Judy Garland for “A Star is Born,” co-starring James Mason and Jack Carson; and Jane Wyman in “Magnificent Obsession,” with Rock Hudson and Agnes Moorehead. When it came time to announce the winner for best actress, presenter William Holden took the stage. Many assumed he would filibuster to keep the audience in suspense. However, when he reached the podium, all he said was, “Because time is running short, the ‘Best Actress’ Oscar goes to Grace Kelly, for ‘The Country Girl.’” Dottie was shocked and terribly disappointed. She had fought tooth and nail to even get the part as Carmen Jones, and at least hoped her friend Judy would have won it instead. The competition had been fierce though; Garland was a legend, Hepburn a soon to be icon, Wyman was Mrs. Ronald Reagan, and Kelly went on to become the Princess of Monaco. With her career reaching a new height, Dorothy was now commanding a salary as high as some white actresses. With the money, she bought a home overlooking Los Angeles and her name remained in the papers. But not all of the publicity was positive. In 1957, Hollywood Confidential ran a story about an alleged affair between Dandridge and a bartender in Lake Tahoe. She sued the publication successfully for libel. Despite the success of “Carmen Jones,” Dottie’s personal life left something to be desired. She would often go out for a night on the town with best friend and former sister-in-law Geraldine Pate Nicholas Branton, who had been married to Harold’s brother. Dorothy’s sister Vivian would also dine out with them. However, her career was in the doldrums, and she resented being known as “Dorothy Dandridge’s sister.” She was insanely jealous and drank heavily, often causing scenes in public. Dottie felt sorry for her sibling, and tried to help her financially. Dorothy, now heavily involved with the married Preminger, devoted her life to him. He claimed his current marriage was a loveless one, and that his wife had open affairs. Dandridge felt he was the love of her life, and hoped they could someday get married and live in Europe, where bi-racial relationships were more accepted. Unfortunately, Preminger flaunted his wife at movie premiers, making Dottie uneasy. Dandridge next starred in the movie “Tamango,” and it was a minor hit. Dorothy then attended the Cannes Film Festival with Preminger, after which she returned to the u.s. for more nightclub work as she awaited her next film offer. The actress was then asked by prolific film producer Darryl Zanuck to play Tuptim in the big-budget musical “The King and I,” but Preminger convinced Dorothy she deserved more than a supporting role. Actress Rita Moreno won the part, and the film was a huge success. This strained Dorothy’s relationship with Otto, and the affair that had remained behind closed doors for several years, ended disastrously. In 1957 Zanuck asked Dottie to play Margot Seaton in “Island In The Sun.” The movie dealt with two interracial relationships, involving Dorothy’s character and white actor John Justin, as well as an affair between Joan Fontaine and Harry Belafonte. It was a successful picture due to it’s controversial subject matter, but dismissed by critics as being boring. In 1959, MGM mogul Samuel Goldwyn announced that he would film George Gershwin’s musical “Porgy and Bess.” The story was highly unpopular with blacks, who thought it to be stereotypical. When Harry Belafonte and Dorothy were asked to star in the lead roles, Belafonte turned it down. Dorothy did not want to do it either, but reluctantly accepted because no other movie offers were coming her way. Sidney Poitier was cast in Harry’s place, with Sammy Davis, Jr. co-starring. The director was to be Reuben Mamoulain, but he was replaced at the last minute, much to Dottie's chagrin, by Otto Preminger. He was particularly harsh with Dorothy during the filming. He criticized her acting and her having to use artificial tears. His reprimands were often so cruel and embarrassing that Dottie would rush from the set — ironically in tears. He began shooting one scene by dryly saying, “Finally, real tears.” Despite the difficulties she faced while filming, Dorothy won a Golden Globe Award for her performance. She re-entered the nightclub scene, and soon met a down-and-out, yet debonair white restaurant owner named Jack Denison. He pursued her relentlessly, and told her a sob story of how he had been involved with a black woman who died tragically. In reality, he had abandoned her and their child. The two basically starved to death. Dottie’s friends tried to convince her not to marry Denison. They told her he was just after her money. Despite the warnings, the two wed on June 22, 1959. He not only controlled her career, but made her cut ties with friends, including manager Earl Mills. Dension would often beat his wife, causing movie make-up crews to work to cover up Dorothy’s bruises. On top of this, an oil investment that Dandridge had entered into with other Hollywood stars turned out to be a scam and she lost a large sum of money. Dottie also discovered that the people who were handling her finances had defrauded her of $150,000, and she was $139,000 in debt for back taxes. Her business manager at the time was a man named Jerome Rosenthal. Years later he would be found liable by a California court for a massive $22.8 million judgment in favor of a former client of his, Doris Day. In 1961, Dorothy happily appeared on the “Ed Sullivan Show,” but few other television appearances would follow. To alleviate her troubles, Dorothy began to drink heavily. She moved into a small apartment at 8495 Fountain Avenue in West Hollywood, California. In August of 1962, her long-time friend Marilyn Monroe died of a mysterious drug overdose. Dottie had remained close to the tragic star up until the end and commented, “I never thought of Marilyn as a tragic figure. She was full of joy and excitement for living. Sure she had her moods, but mostly she was a happy girl. Her problem was in believing. She believed people even after they disappointed her over and over.” On April 26, 1963, Dorothy declared bankruptcy. She had to sell her home, two cars, and owed 77 bill collectors $127,994.90, a monstrous sum back in those days. Her daughter Lynn was also dropped on her doorstep by authorities, because she was unable to pay the costs of her private institution. The child, now 17, did not respond to her mother, and would only play one note on the piano, for hours straight, while Dorothy sobbed in her bedroom. She was now faced with the hardest decision of her life: What to do about her daughter’s care? Dottie agreed to drop her parental rights and made her daughter a ward of the state, placing her in an institution in Camarillo, California. Then Dorothy moved into a small apartment at 8495 Fountain Avenue in West Hollywood. She continued to drink to excess and would call friends at all hours of the night, unable to sleep and hopelessly depressed. She finally filed for divorce and tried to get her life back on track. Doctors prescribed her an antidepressant, which seemed to greatly help. In 1964, Dottie reconciled with manager Earl Mills, who helped to resurrect her flagging career. She attended a health spa in Mexico, toured spots there and in Japan. Dandridge had plans to go to New York, but sprained her ankle, fracturing her foot. On the morning of September 8, 1965, Dorothy had an appointment to have a cast put on. Mills phoned her early in the morning, she she requested he call back later, as she had been up all night. He phoned again in the afternoon, but there was no answer. Finally, a concerned Mills went to Dottie’s apartment, but she did not answer the door. He returned around 2 p.m. and forced his way in. He found his client lying nude on the bathroom floor with only a blue scarf around her head. He called out her nickname, “Angel Face.” But Dorothy Dandridge had expired several hours before. She was 42 years old. A few months prior to her death, Dorothy had written a note in May, which read: “In case of my death — to whomever discovers it — don’t remove anything I have on — scarf, gown or underwear. Cremate me right away. If I have anything, money, furniture, give it to my mother Ruby Dandridge. She will know what to do. (Signed) Dorothy Dandridge.” She gave Mills the note, saying, “You keep it Earl, because I know you will be the one who discovers me.” Because Dorothy had made no prior arrangements, the note became her Last Will and Testament. Even in death, racism was still ever present. The authorities on the scene referred to Dottie as “that colored singer.” And despite mixed heritage, her race was listed on the death certificate simply as “Negro.” At first it was believed Dorothy died from a blood clot caused by flanks of bone marrow clumping in her ankle. The question of suicide was posed, mainly due to the cryptic note. However, an autopsy revealed that the cause of death was due to an overdose of Tofranil, the antidepressant she had been taking at the time. Most friends concluded Dandridge would never have committed suicide. Her estate consisted of $4,000 worth of furniture and she had only $2.14 in her bank account. Dottie was cremated and buried at the Little Church of the Flowers at Forest Lawn. Ironically, she had just completed an autobiography, and would have given the profits to charities for mentally retarded children. In 2000, Earl Conrad co-authored and published the memoir, to mixed reviews. It is entitled “Everything and Nothing: The Dorothy Dandridge Tragedy.” Other biographies have been written about the star, including a revealing book by manager Earl Mills. Posthumously, Dorothy received a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, and was placed in the Black Film Hall of Fame in 1977. Her mother Ruby died in 1987, and is buried next to her. Father Cyril passed away in 1989, and sister Vivian in 1991. Dorothy’s daughter, Lynn, a woman in her 60s, still lives in an institution. In 1999 an HBO made-for-TV-movie was released entitled “Introducing Dorothy Dandridge.” Halle Berry was chosen to portray the actress. Hale described Dottie this way: “You have to find a way to be sad on every day, in every scene, in every moment. And always try to hide the sadness. And (then) you’ll get the essence of who she was.” Many critics and fans also pointed out how much Berry resembled the late star, not just appearance-wise, but how they both battled racism in their careers. Coincidentally, Berry is a fellow Clevelander. The movie won five Emmy awards. Berry won a Golden Globe Award and a Screen Actors Guild Award for her performance. In Halle’s acceptance speech, she honored the women who had come before her: A door that Dandridge helped open; however, she never got the chance to walk through it. In her own words Dottie reflected,“[Prejudice] is such a waste. It makes you logy and half-alive. It gives you nothing. It takes away.” In her case, it not only took away career advancement, but ultimately drove her to self-destruction and into obscurity. Dorothy is in many ways like a lotus plant that grows in wet, muddy conditions, only to reach the surface of the water and blossom into a beautiful flower. Some say if she had been born 20 years later she could have been a household name. But Dottie wasn’t destined for that. She hit all the potholes on the road to success, patching them along the way, so future artists could have the opportunities she was not allowed. Because of that, Dorothy Dandridge’s contributions to society bloom in other ways. Copyright 2009 by Midwest Today. All rights reserved. |

||

Many filmgoers today are not familiar with Dorothy Dandridge. She lived in the shadow of her white contemporaries, but made great strides for the African American community, paving the way for future bi-racial performers. As a singer who went into acting, she spent her life breaking racial stereotypes, and concert attendance records. But it wasn’t until director Otto Preminger cast her in the lead in the film “Carmen Jones” that she truly achieved stardom. Because of that role, she became the first black woman to be nominated for a “Best Actress” Oscar. It would be another 47 years until Halle Berry would actually win one.

Many filmgoers today are not familiar with Dorothy Dandridge. She lived in the shadow of her white contemporaries, but made great strides for the African American community, paving the way for future bi-racial performers. As a singer who went into acting, she spent her life breaking racial stereotypes, and concert attendance records. But it wasn’t until director Otto Preminger cast her in the lead in the film “Carmen Jones” that she truly achieved stardom. Because of that role, she became the first black woman to be nominated for a “Best Actress” Oscar. It would be another 47 years until Halle Berry would actually win one.